A New Attempt to Solve the Amelia Earhart Mystery

In November, a team from Purdue University will travel to the south Pacific Ocean to figure out if an object seen in several satellite photos is a felled palm tree or the long-lost aviator's Lockheed Electra.

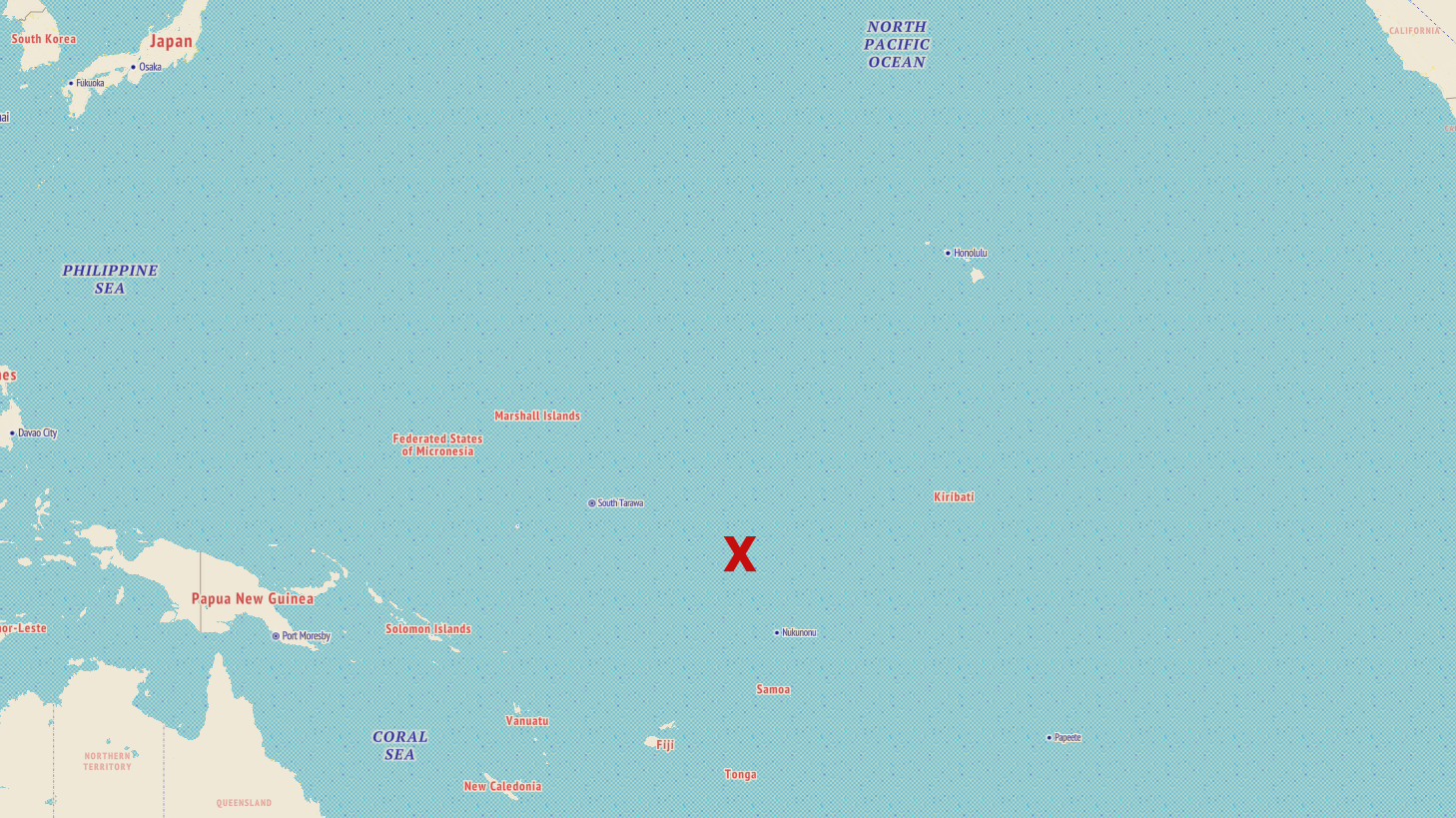

Nikumaroro Island (map: Mapbox)

Purdue University in the US has announced a new expedition to find Amelia Earhart’s plane. Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, disappeared 88 years ago, on 2 July 1937 in the south Pacific Ocean. A field team from the university will be dispatched on 5 November to the small island of Nikumaroro (known as Gardner Island at the time of Earhart’s flight), which is part of the remote Phoenix Islands chain in Kiribati (Micronesia).

Location of Nikumaroro Island, Kiribati in the south Pacific Ocean (composite graphic / map: Mapbox)

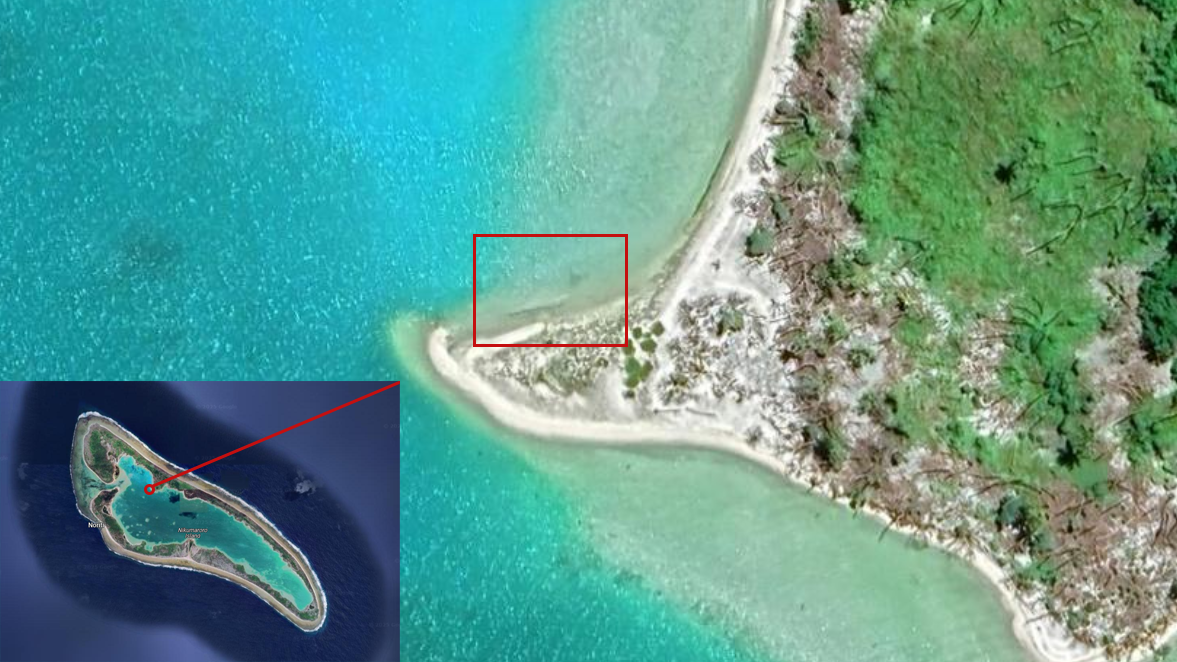

The group’s mission is to investigate the so-called Taraia Object, which is thought to be the remains of Earhart’s Lockheed Model 10E Electra airplane. The Taraia Object is situated within the lagoon of Nikumaroro Island and was initially noticed in 2020 on satellite imagery provided by Apple Maps.

The Object was brought to our attention by Michael Ashmore, who observed it initially in 2020 in an Apple Maps image captured by satellite. Subsequent to that, Archaeological Legacy Institute (ALI), with funding from a small group of donors, obtained a series of 26 additional satellite images spanning the time between 2009 and 2021. Subsequently, ALI acquired three more satellite images from Google Earth, spanning the time from 2022 through 2024. In these satellite images, the Object first becomes visible on April 27, 2015, a time shortly after Topical Cyclone Pam passed by the island in late March 2015. This storm, one of the most powerful ever recorded in the south Pacific Ocean (Hoekel et al. 2021), generated severe storm-surge impact on Nikumaroro, uprooting many trees along its western shore, as shown by satellite imagery. This storm surge approached the island from the west, no doubt sweeping into the lagoon, apparently removed sediment that had covered the Object, and made it visible from above. The Object is most sharply defined in 2015 and 2016, then becomes less sharply defined by 2020 and 2021, and appears in images from 2022 through 2024 as a recognizable shape probably covered by a thin veneer of sediment.

The Taraia Object in the lagoon of Nikumaroro Island (composite graphic based on satellite imagery from Google Maps / Airbus / Maxar Technologies)

One of the reasons that this grainy object is being considered to be the remains of Earhart’s plane is that Nikumaroro was long thought to be the place where the famous female aviator crashed. This is mostly based on investigative work, based on public domain evidence, done by the non-profit International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR). Some of the conclusions drawn from the evidence have been disputed. In 2019, TIGHAR organised an expedition, led by Bob Ballard, to the island that, eventually, returned empty handed.

Robert Ballard, the ocean explorer famous for locating the wreck of the Titanic, led a team aboard the resesearch vessel Nautilus that discovered two hats in the depths. It found debris from an old shipwreck. It even spotted a soda can. What it did not find was a single piece of the Lockheed Electra airplane flown in 1937 by Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan, which vanished during their doomed voyage around the world.

Dr. Ballard had avoided the Earhart mystery for decades, dismissing the search area as too large, until he was presented with a clue he found irresistible. Kurt Campbell, then a senior official in President Barack Obama’s State Department, shared with him what is known as the Bevington image — a photo taken by a British officer in 1940 at what is now known as Nikumaroro, an atoll in the Phoenix Islands in the Republic of Kiribati. American intelligence analysts had enhanced the image at Mr. Campbell’s request, and concluded a blurry object in it was consistent with landing gear from Earhart’s plane.

Dr. Ballard and Allison Fundis, the Nautilus’s chief operating officer, coordinated an elaborate plan of attack. First, they sent the ship five times around the island to map it with multibeam sonar, and deployed a floating autonomous surface vehicle to map shallower areas off the island’s shore. They also used four aerial drones for additional inspections of the surrounding reef.

At that point, the crew focused on the northwest corner of the island near the S.S. Norwich City, a British freighter that ran aground on the island in 1929, eight years before Earhart’s disappearance. That is the area where the Bevington photo was taken. While they searched there, crew members found so many beach rocks consistent in size and shape with the supposed landing gear in the Bevington image that it became a joke on the ship. “Oh look,” Dr. Ballard would chuckle, “another landing gear rock.”

Ms. Fundis said, “We felt like if her plane was there, we would have found it pretty early in the expedition.” Still, Dr. Ballard and Ms. Fundis confess that other clues pointing to Nikumaroro have left them with lingering curiosity about whether Earhart crashed there.

Cf.: TIGHAR analysis of the Bevington photo

But even TIGHAR’s executive director, Richard Gillespie, doubts that the Taraia Object is Earhart’s plane or parts thereof.

Gillespie has launched a dozen expeditions over the last 35 years searching for Earhart, including searches of Nikumaroro. He said the satellite image guiding the Purdue expedition shows an overturned coconut palm tree with a root ball that had been washed up by a storm.

“I understand the desire to find a piece of Amelia Earhart’s airplane. God knows we’ve tried,” he said. “But the data, the facts, do not support the hypothesis. It’s as simple as that.”

Despite his skepticism, Purdue will undertake the expedition regardless. The Purdue Research Foundation has extended a credit line of $500,000 to the first phase of the expedition […] The expedition members will depart in November and spend six days traveling to reach Nikumaroro. From there, they’ll have five days on the island to investigate the object from the satellite imagery and determine whether or not it is evidence of Earhart’s missing plane.

I guess we will find out in November. Or, just as likely, this 88 year mystery will continue to puzzle us for a while longer.